Welcome to our series, “Women of Isle Royale,” where we celebrate and highlight the lives and legacies of the remarkable women who shaped the history of this unique island. These women are central to the life and community of Isle Royale. They were not only integral to the fishing, resort, and conservation efforts, but they were also keepers of culture, family, and tradition. To catch the latest, follow us on Instagram @isleroyalers

Edith Foster Dulles (1863-1941)

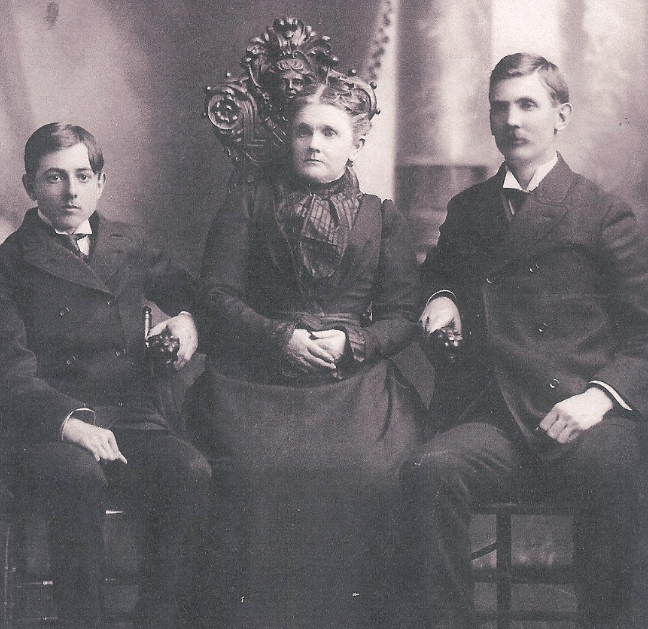

Photos from the edwards family collection

Edith Foster Dulles had the distinguished status of being the daughter of a Secretary of State {John Foster/President Benjamin Harrison}, the mother of a Secretary of State {John Foster Dulles/President Dwight Eisenhower} and the sister-in-law of a Secretary of State {Robert Lansing/President Woodrow Wilson}. As the daughter of a diplomat, Edith grew up as a world traveler and was described as a civic leader and social worker throughout her adult life. Her grandson described her as “strong… a person of gracious charm, marked executive ability, and a wisdom born of long experience.”

She visited Isle Royale in the summer of 1912, as chaperone to her daughter Margaret Josephine Dulles, engaged to Deane Edwards, Edwards Island. Their courtship resulted in marriage the following year. On August 12, 1912, Edith attended the housewarming of “Prospect Camp” celebrating with other islanders the completion of the new Edwards Cabin which still stands today and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. While on Edwards Island, Edith penned a poem in dedication to the “campers at Edward’s Island” entitled “The White Rag”, “in grateful remembrance of a delightful week.”

The White Rag

When on lovely Isle Royale you’re standing,

By the table that’s empty of food,

Use the little white rag I am leaving

And scrub all the fine dishes good

When the water’s too hot for your fingers

Just take a look out o’er the lake,

If ever the pleasant task lingers

Think of me for the little rag’s sake

When far from your island I am living

My thoughts to that table will fly,

And the fresh air again I’ll feel blowing

And long for the things one can’t buy

~ E.F.D August 15th 1912

Alfreda Gale (1892-1980)

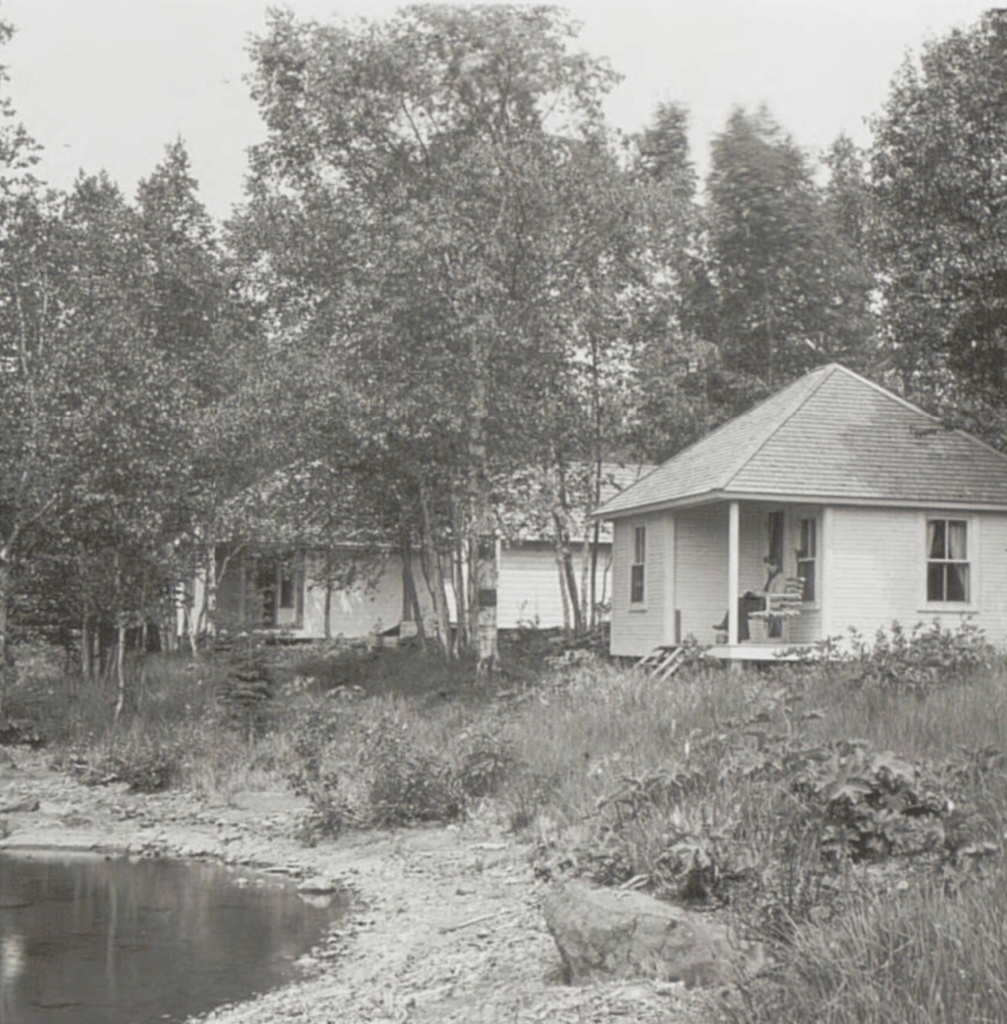

Alfreda Prince Gale was born in New Jersey to Alfred and Mary Prince. They soon moved to St. Louis, MO and created a new life in the Midwest. Alfreda was married in 1915 to Austin Gale and had two sons John and Phil. In 1932, the same year her mother died, Alfreda was invited to visit Isle Royale by her good friend, Gertrude How, whose family owned an island in Tobin Harbor. She was fascinated with Isle Royale’s wilderness and loved the community of fishing families, summer residents, recreationists, resort guests, and lighthouse keepers. So much so that the next year she brought her two sons, John and Phil, and rented the upstairs of the Musselman’s cabin. In 1934, Alfreda invited her father, Alfred, to come with her and the boys to the Island. The next year Alfred bought Gale Island in Tobin Harbor (~2.5 acres). As a note, her father Alfred died on Gale Island in 1946 after cutting alders.

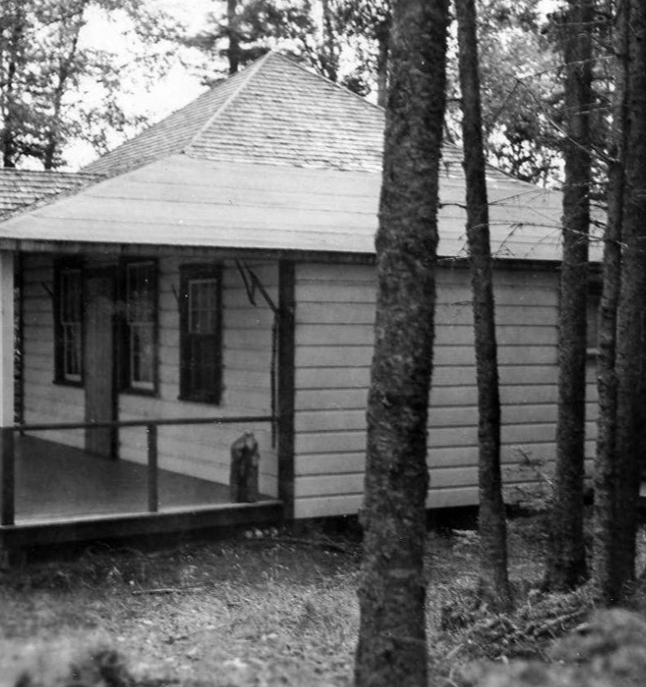

photos from gale family collection

Alfreda treasured her new friendships and loved exploring the landscape of Tobin Harbor and Isle Royale. During WWII, she coordinated a camping trip with other Isle Royale women circumnavigating Isle Royale for five days in a 28 foot open launch. Alfreda was a very independent single mother, learning how to run many outboard motors, how to cut wood, and the use of basic tools needed to maintain the cabin (built in 1937). Yet, she always wore a dress with stockings, worn to keep biting flies off her legs.

Alfreda was a very good cook and loved socializing and organizing picnics to different parts of the Island. She loved bringing her seven grandchildren to the island; they fondly called her Mother Gale. Alfreda’s religious background in the Swedenborg church (which teaches that the natural world reflects spiritual realities providing deeper meaning to everyday life) fit well with her life on Isle Royale. She was close to 80 when she visited the Island for the last time. Six generations of Gales and many other guests have enjoyed Isle Royale through Mother Gale’s adventurous spirit.

Lucile Ziegler Snell (1891-1982)

Lucile Ziegler Snell. Born in 1891, raised in Sioux City, Iowa, she was a 1915 graduate of the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. She went on to teach piano at several colleges. The Snells came to the island in 1931 in search of respite for her asthma and hayfever. Their three boys kept her busy at their cabin in Tobin Harbor. The family lived the rest of the year in Wheaton Illinois a suburb of Chicago so Isle Royale was a great escape from that. At the island Lucile learned to run a motorboat as travel by water was the only way to connect with her harbor friends.

Life was pretty basic and most her time was spent on preparing food and baking from scratch. “We never got a chance to see if we liked pike fish since mother thought they were too ugly for her to deal with. I seem to remember that we had our big meal at noon which was not so uncommon in those days,” remembered Laurie Snell. In her spare time she sewed. She made ‘ditty bags’ for selling at the Rock Harbor Lodge as well as curtains, chair cushions and braided rugs. There was not a piano or organ at the Snell Camp but there was at the Lodge and the Tobin Harbor Resort across the way and she was often called on to play for special events or religious services. Of course for most of women in the harbor, this was their home, more than a vacation place.

Continuing to live and look ladylike mattered too, even in the woods and in a cabin. “Grandma did wear blue jeans during the day. But every evening she got all cleaned up, using pitcher and bowl, and put on a pretty pink robe before their nightly game of Canasta or Crazy Eights. She was no slouch at scrabble either.

Mostly of course we ate fish. A great slab of bacon lived outside in the ‘California cooler’ which is a small crate-like box nailed to a tree with its own little screen door to keep out the squirrels and chipmunks. We ate lots of crackers” remembered Joan Snell.

Lucile spent summers at the island from 1931-1960. After Grandpa Snell died she moved into an apartment in Wheaton. She would come to the island every chance she got, coming back to, as she put it, “the only home I have now.”

Catherine Bowen Johns (1845-1911)

Catherine was born in 1845 in Cardiff, England and immigrated to Calumet, Michigan in 1862 at the age of 17. There she met and married her husband John F Johns in August of the same year. They arrived at Isle Royale in the 1860’s and had 11 children, one of whom, Raymond born in 1878 at McCargo Cove, passed away and is buried there. In recountng the story of his birth their youngest son, Edgar R Johns, said his father was worried about Catherine giving birth to an 11th child on Isle Royale so he sent her to her aunt’s home in Superior Wisconsin for the birth. But just two weeks later, Catherine was back on Isle Royale carrying on her work.

And what was her work? She wasn’t just a mother. She was also the resident doctor and cook for the miners. According to Edgar, “my father cut his toe off, kicked his boot off then got a hold of the toe and put it back on again and bandaged it up. Yes, he did it himself. He then hollered for Catherine – my mother came out and she was like a nurse. All of the men on Isle Royale when they got sick from too much drinking, she would always doctor them up. And some of them would cut themselves and she would sew it up just like a doctor. She was good.” When John F. Johns was asked to be the captain of the Windigo Mine, he and Catherine moved down to where the two big boarding houses were built – one was for all the unmarried miners. Every day, Edgar said, “she used to make forty pasties – they wouldn’t have nothing else and they did not want pie….what they wanted was apple pasties. She used to make big ones – I remember the pans – and she would cut them in half and then in half again and put it in their big lunch pails…A whole meat pasty and a pot of tea. That is all they wanted and they swung those darn hammers and drills all day long. She would make scones and cream.” In 1892 Captain Johns and Catherine opened the Johns Hotel, the first summer resort on Isle Royale, which is now listed on the Natonal Register of Historic Places and cared for by their descendants.

Credit to Cindy Johns Giesen for her contribution to this post.

Frances Andrews (1884-1961)

Photos courtesy of NPS.org and Hunt hill

Frances had a love of the wildness and beauty which fed her interest in conservation, education and social justice. Frances used her money and social contacts to support projects like the development of the Boundary Waters as well as encouraging the preservation of Isle Royale as a place of tranquility and peace for all. She worked with Aldo Leopold, Ernest Oberholtzer, Roger Tory Peterson, Owen Gromme, Ernie Swift, and many other conservationists. Ober was a frequent visitor at the island and when Frances passed he did a paddle their in her memory.

The family began going to the island around 1898 and every summer thereafter for fifty years. Arthur was in the grain business in Minneapolis, there his wife Mary Hunt, and his family enjoyed a high standard of living. Besides the Isle Royale cottage on Barnum Island, they also owned land in Rainy Lake and Hunt Hill in Sarona, WI.

The Sivertson family lived and worked near the Andrews. On one occasion when she took a group hiking she was observed, “’Now everybody lay down’. She lay spread eagle on the ground to rest and everyone had to do the same. “We can hike all day like this.” she said. She wore denim hiking clothes and had her pince nez hanging from her neck.” Howard Sivertson said in an oral interview.

“My most remarkable memory of Frances Andrews was associated with a musical event. My dad played his concertina, Linnea Eckle, my aunt sang ‘I love you truly’ and other songs, in a beautiful contralto voice, with the mostly women and kids, and a few fishermen of the harbor assembled on the lawn of Barnum Island facing Sunset Rock, which was reflecting the afternoon sun and was echoing the music across the harbor. Frances rewarded us kids, seated obediently in a large circle, giving out shelled peanuts with a demitasse spoon. It is one of my most beautiful Isle Royale memories.”

Frances funded the construction of the dock in front of the Grand Portage Stockade used by the Wenonah for many years, also the highway construction providing motor access to Grand Portage. She was a great lady, fun to be around, and she knew how to row a boat.” Stuart Sivertson, email conversation.

Tchi-Ki-Wis (1875-1935)

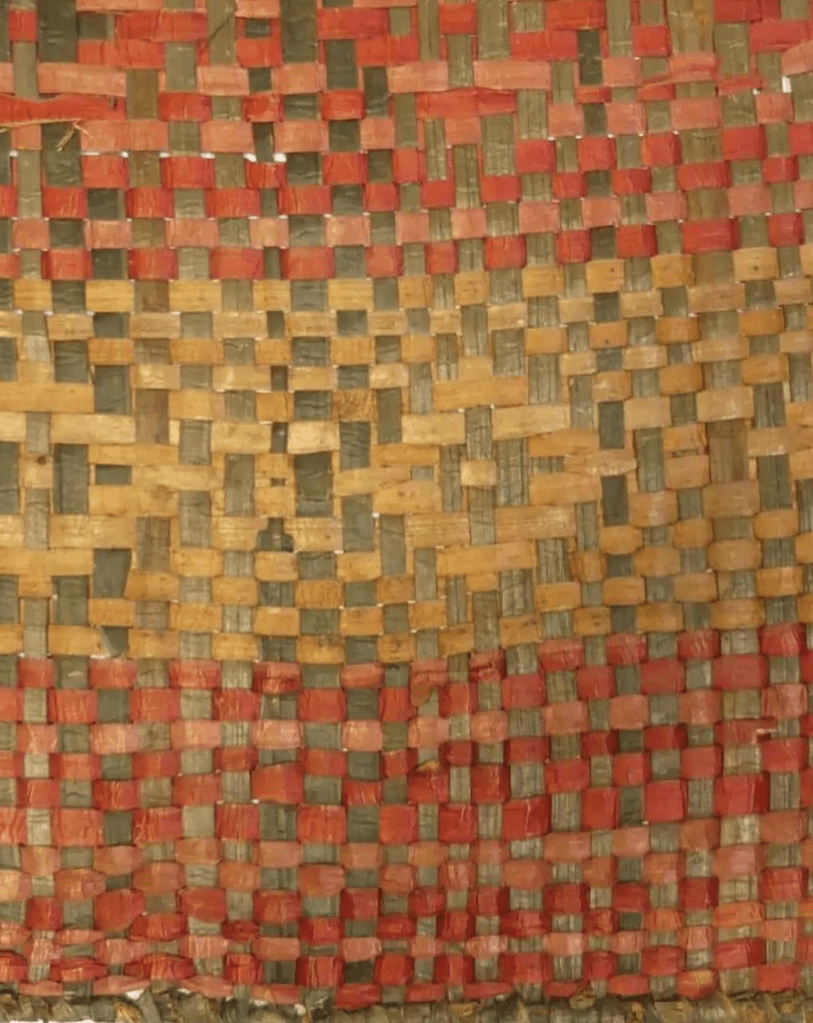

Photo courtesy Warren/Anderson collection, Isle Royale National Park, and Ellie Connolly IRFFA member

Tchi-Ki-Wis’ family were Lac La Croix First Nation tribal members. She lived with her husband Jack Linklater on Basswood Lake in Minnesota and Birch Island located in beautiful McCargo Cove at Isle Royale. They had two daughters. Tchi-Ki-Wis made moccasins, tumplines or portage collars, bead and quill work, birch-bark baskets, tanned hides, cedar bark mats, birchbark canoes and more. She was extremely generous and gifted or sold these handmade objects to people who showed an interest in them. She also helped Jack with fishing and pulling nets. For more information on her life read Timothy Cochrane’s new book “Making the Carry: The Lives of John and Tchi-Ki-Wis Linklater.” Also John (Jack) Linklater Legendary Indian Game Warden by Sister Noemi Weygant.

Sally McPherren Orsborn

Island traditions run deep, and at 92 years young, nothing stops Sally McPherren Orsborn from returning to Captain Kidd Island on Isle Royale’s North Shore, where she has summered since she was 4-years-old. Sally and her sister Elinor grew up swimming, reading, fishing and boating on Isle Royale; playing the ukulele passed time, curbed isolation and brought enjoyment. As a teenager, Sally waited tables at the Rock Harbor Lodge where an acquaintance with Jack Orsborn of Snug Harbor turned to romance and ultimately a 62-year marriage. Today, Sally’s children and grandchildren also feel the pull of Captain Kidd, continuing a family pattern rooted in the simplicity of island living. Photos courtesy of Carla Anderson and Sally Orsborn Collections.

Alice Love Merritt

Alice Love Merritt first came to Isle Royale as a guest of her future husband, Glen Merritt, the son of Alfred Merritt. Alice loved Isle Royale and, every January, started packing boxes for the annual summer adventure to Tobin’s Harbor. She spent her time on Isle Royale baking, knitting, and caring for her family. She was patient with her grandchildren and loved teaching them how to use the wood stove, pick berries, and properly light a kerosene lamp.

Alice could worry better than almost any grandmother on the planet. Everyone in the boat had to remain seated and keep their fingers inside until it was safely moored.

Alice was also very good at telling Glen how to steer the boat properly. There was trouble on one memorable trip to Passage Island to get rhubarb from the lighthouse keepers. As with most trips to Passage, the winds were calm, and the skies were blue on the voyage. But before the return, the wind started blowing, and the fog crept over Blakes Point. With my Grandfather at the helm of the old 19’ wooden “Handy,” Alice stood up in the bow, holding on to the bowline for stability, scanning the water for freighters and deadheads. I was bundled up in old woolen blankets and extra life jackets while curled on the floor. Alice kept one eye on the water and another on Glen. Glen thought he was going the right way but drifted off course in the fog. At her insistence, he steered back towards the mainland. “Glen, there are big waves ahead,” Alice screamed as the Handy bounced over a series of rollers. Looking up, all that could be seen was the stern of a downbound freighter out of Thunder Bay, navigating between Passage Island and Blakes. Needless to say, there were fewer trips anywhere in the fog!

Alice loved Isle Royale; she loved the community of Tobin’s Harbor more. In 1980, she told Glen that she wouldn’t return to the Island, thus ending her time there. Alice lived another 18 years and died 3 months shy of 100. Isle Royale isn’t the same without her, but her memory and blueberry pie recipe live on.

Contributed by Brian Bergson – photos from Brian Bergson and the Merritt Family.

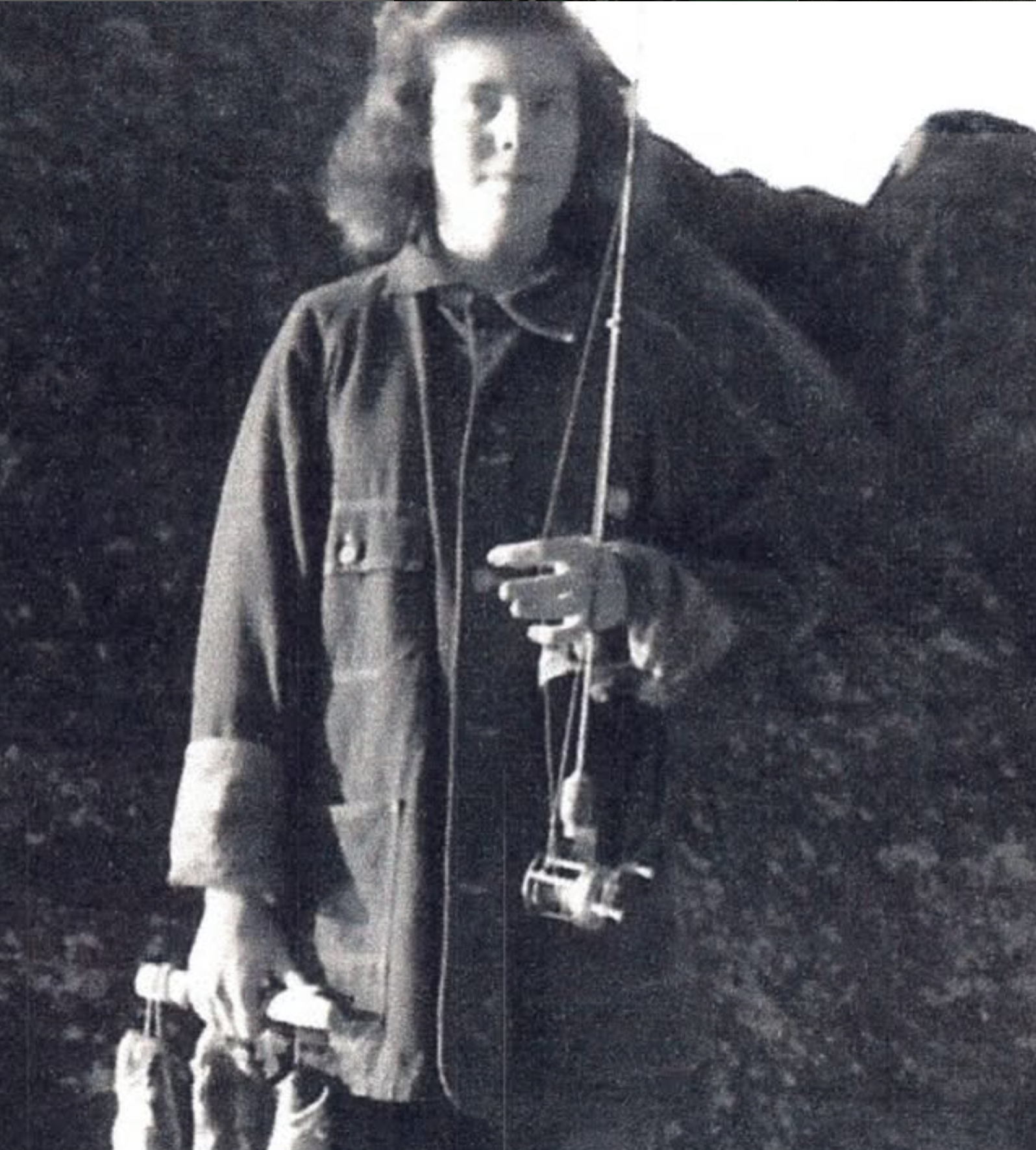

Edith Brown Coventry (1890-1961)

Edith Brown Coventry (1890-1961), born in Duluth to John and Charlotte Coventry. Edith loved hunting, fishing and all-around adventure. A single woman who never married, she had the moxie to purchase a small island in 1918 on the north side of Isle Royale, south and east of Belle Isle, from fellow Duluthian, Worthington S. Telford an attorney, chair of the Citizens Training Camp Association and recruiting officer for the R.O.T.C in Duluth during World War I. While she did not own her island long, Edith was an active member of the community in Belle Harbor. Many photos exist of her time on her island. They include shots of her with guests of the Belle Isle Resort, socializing with the local fishing family from Johnson Island, standing in front of her log cabin, in her canoe and holding fish. Edith owned the island until around 1923 when she moved to Florida and established one of its first photo studios, the Edith Brown Coventry Kodak Finishing Shop, in 1922, and later another shop, E.B. Coventry, which she operated for many years. Edward Fisher, for whom the island is known today, eventually purchased it from her.

What inspired a single woman to buy and live on a remote island in the middle of Lake Superior? While we do not know all of the details about Edith’s life, we do know that her story is not unique. She is representative of other early 20th-century unmarried women who also found a safe haven in island-living on Isle Royale. Edith and others broke traditional gender roles, displayed independence and found acceptance from island communities. These stories often slip through history’s cracks, yet their importance is no less significant. In fact, by uncovering gaps in the Isle Royale story, they enrich and contribute to our understanding of a more complete cultural history of the island. Future posts will highlight more untold stories like Edith Coventry.

For more photos of Edith’s time on Isle Royale and in Florida see: https://www.martindigitalhistory.org/collections/show/20.

Photos Credits: Edith in front of log cabin, the Anderson Family collection from Johnson Isle.

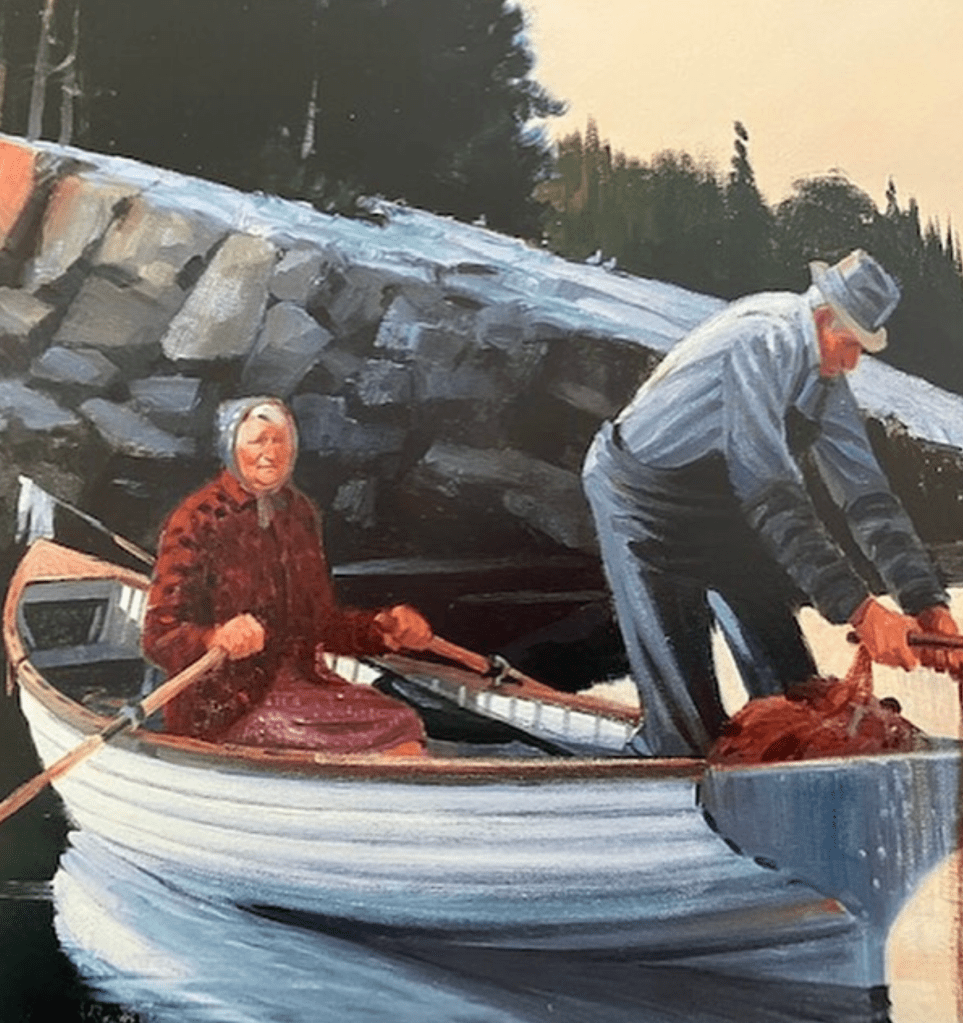

Theodora Christiansen Sivertson

“I remember her especially as the quiet strong center of things, an unobtrusive core of love that everything else seemed to move around,” wrote Howard Sivertson about his grandmother Theodora Christiansen Sivertson of Washington Harbor, Isle Royale. Theodora, called Dora or T’dora, was born in Egersund Norway. Her life changed when she emigrated in 1892 to Minnesota to marry Severen “Sam” Sivertson who began commercial fishing on Isle Royale soon after.

T’dora became the matriarch of an island fishing community, most with Scandinavian roots, that numbered over 75 families in the 1920s. She always wore a flowered dress, an apron, a thick, warm sweater, cotton stockings and sturdy black shoes with a white dish towel flung over her shoulder for waving. Her four children all raised on Isle Royale carried on the family tradition of commercial fishing.

Gardening was a passion, but one often found T’dora cooking on the woodstove, the centerpiece of cabin living. The daughter of a restauranteur in Norway, T’dora was known for her fish cakes, sweet pickles, lemon souffle and delicious rye bread. And at least once, that rye bread produced unexpected results. Thinking she had emptied a box of raisins into the dough, instead, she had reached into the dark pantry and mistakenly baked a box of buttons into the bread!

Fisherman’s wives worked hard minding children, keeping the home fires burning and contributing to the family livelihood, but often found a respite in the weekly routine to row across a familiar water route to socialize together. These gatherings reinforced their shared circumstances bonded by familial ties, ethnicity and island living.

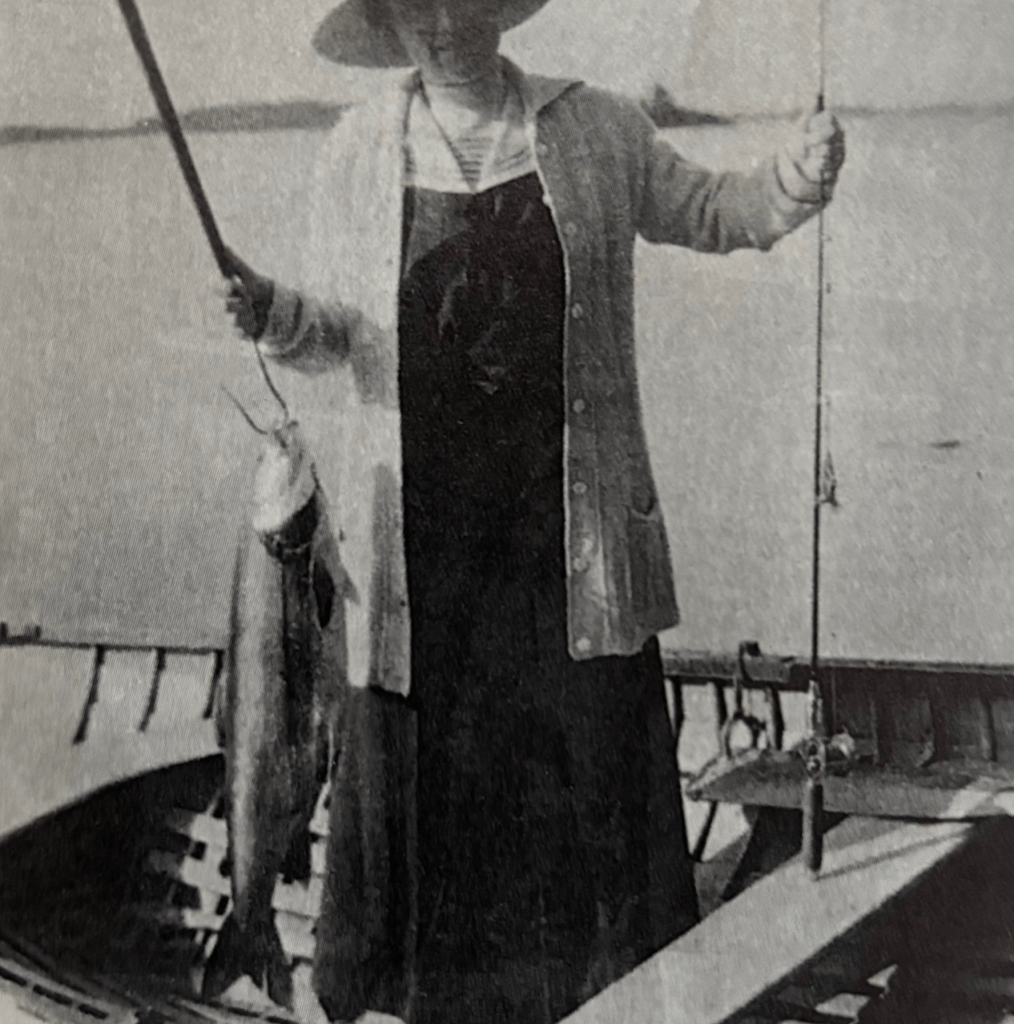

In her later years, T’dora often rowed Sam several miles each day in order to set a few nets and enjoy the familiar rocking motion of the water. Family and friends, children and grandchildren, revolved around T’dora’ caring nature. The coffee pot was always on and visitors were always welcome! Photos from Betty Strom collection. Painting is by Howard Sivertson.

Bertha Nuetson Farmer (1880-1966)

We remember Bertha Nuetson Farmer (1880-1966), manager of Rock Harbor Lodge from 1922-1942. Bertha was the first child of Kneut Neutson and Theresa Neutson. Bertha’s father came to Isle Royale in 1898 and he purchased a mile of frontage along the shores of Rock Harbor. In 1901 Kneut Neutson created one of the eight hotels on the Island, Park Place Resort. Tourism was flourishing on Isle Royale and the “Commodore” could not handle all the work needed to maintain Park Place Resort so he made his daughter Bertha the new Manager and renamed the resort Rock Harbor Lodge. Bertha was instrumental in upgrading the Lodge and adding many new buildings including the Guest House which is still standing today.

Bertha also raised a family with her husband Matt. She had three children, Westy, Theresa “Sis”, and Edith. Bertha’s and Matt’s five grandchildren were born in the 1920s. Many people including resort owners and summer residents in Rock Harbor and Tobins Harbor worked on preserving Isle Royale as a natural resource and as a Federal Park. The Isle Royale Citizens’ Committee of Isle Royale was organized in 1919 (subsequently renamed The Isle Royale Protective Association in 1931) with Bertha as a key player in supporting the idea of a state or National park. The Enabling Legislation to create Isle Royale as a National Park was enacted in 1931. After this occurred, Bertha became not only the Manager of Rock Harbor Lodge but also of Belle Isle Resort, Minong Resort, and the part-time store at Mott Island. She also provided support to the CCC camp from 1936-37. In 1942, the National Park replaced Bertha as manager of Rock Harbor Lodge with the National Park Concessions, Inc. This company replaced a person whom many felt was the cultural essence of Isle Royale Resorts.

Information and Photographs were taken from: John J. Little, PhD Dissertation, Island Wilderness : A History of Isle Royale National Park – University of Toledo 1978; Amalia Tholen Baldwin – Becoming Wilderness: Nature, History, and the Making of Isle Royale National Park; T.P. Gale and K.L. Gale – Isle Royale – A Photographic History 1995. Dan Farmer (Great Grandson); Ancestry.com

Myrtle Weart

Continuing with Our Women of Isle Royale, today we tell the story of Myrtle Weart and her well traveled organ. Myrtle and her husband Peter married in 1891 and had their home in Chicago. In 1908, they built their cottage in Snug Harbor on property they had purchased from Knuet Nuetson. Peter was a dentist and Myrtle was a classical singer and music teacher. Peter passed away in 1927 yet Myrtle continued to visit their cabin each summer on her own which may have been somewhat unusual for a widow at that time. However, it was customary for the island community to accept and welcome widowed and unmarried women like Myrtle who deviated from the societal conventions of cities and urban areas. While she is remembered as a quiet person, Myrtle was an active member of the Rock Harbor community. She was famous for her wonderful fudge that she made each year for the Rock Harbor Regatta. 97 year-old Jean Rockwell, Myrtle’s former neighbor in Rock Harbor, remembers her fudge to this day!

The Weart cabin also had an organ which Myrtle kindly let the daughter of her neighbors, Homer “Coach” & Elizabeth “Angelique” Orsborn, play. When Myrtle sold her cabin in 1938 she gave the organ to the Orsborns and it was moved to their cabin, “The Driftwood”. Eventually, their son, Jack Orsborn, would marry Sally McPherren from Captain Kidd Island. When “The Driftwood’s” life lease holder passed away the Park Service gave the family one summer to clear out their belongings before the cabin was removed. Myrtle’s organ was loaded onto a small boat for transport to Captain Kidd. Rounding Blake Point they encountered huge swells that almost threw the organ overboard. But they made it and today, Myrtle’s organ resides in the double sleeping cabin at Captain Kidd and, but for one sticky key, still works. We don’t have a photo of Myrtle but here is a photo of her organ taken 2 summers ago at Captain Kidd.

Caroline Cooper

A remarkable photograph of an unknown woman on Isle Royale, elegantly dressed, holding up a large devil’s club specimen that takes center stage against a white wooden cottage as backdrop, might intrigue any viewer. Who was she and what was her purpose on Isle Royale? The artful composition draws one’s eye to the devil’s club suggesting the rare, prickly shrub as the photo’s focus, with the woman, her back to the viewer, as a secondary part of the story. With some creative researching and a bit of luck, Caroline Cooper’s story unfolded, capturing a brief, but impactful Isle Royale experience in the summers of 1909 and 1910.

Caroline grew up in Battle Creek, Michigan. Her musical talents took her to the New England Conservatory in Boston, 1876-79, after which she taught piano for many years in Kalamazoo, Michigan. An unexpected encounter with Reverend David Mack Cooper led to marriage at the age of 32, with Cooper 25 years her senior. The birth of son William soon followed. Caroline and son shared a love of the outdoors and spent summers identifying and collecting orchids, mosses and sedges at their summer home on Lake St. Clair. While this led to an academic career for William, it seemed only natural to them, after the death of Caroline’s elderly husband, that she would accompany her son on his research expeditions, the first being on Isle Royale in the summers of 1909 and 1910 to study the island’s vegetation.

During those two summers, mother and son, traversed the island, resulting in a foundational study of Isle Royale’s vegetation. While the published study was William’s Ph.D. dissertation, Caroline played a major role assisting him, as mother, partner, field assistant, helpmate and companion during those rigorous island expeditions. A second photo shows Caroline on Smithwick Island standing next to a birch tree that escaped a recent burn area they examined with unburned forest in the background.

While Caroline’s relationship with Isle Royale was brief, it exemplifies the interest in the

ecological significance of Isle Royale, that has attracted scientific researchers and others for many years who connect with the island in deep and meaningful ways.

Sarah “Sallie” Matilda Thomas Davidson (1874 – 1945)

Sarah “Sallie” Matilda Thomas Davidson was the daughter of a river boat captain. She lived from 1874-1945. Her relationship with the water must have made her times at Isle Royale seem a familiar environment. She and her four children were many times alone, as her husband Watson, a businessman in St. Paul Minnesota, was often working while the family lived on the island in summer. Letters by Sallie to her husband indicate the intricate doings of the local residents of Isle Royale, of course a boat was required. Her granddaughter Cynthia Bend, wrote in her memoir: “My grandmother probably wrote a half-dozen letters every day–you might say she did it out of habit, or, maybe it was a deeper thing, almost a spiritual practice, a way of making an intimate connection with her loved ones when she could not be with them.”

Their property was originally the Tourists Home Resort. In 1910 they bought the island and later constructed their two story house which is now used by the Park Service. They named it Sa Ka Te. The last summer they stayed at the island was in 1934. Again, from Cynthia: ”What I most remember about that small island off the north shore of Lake Superior was my grandmother pointing out to me a “ghost plant,” a moist specter of white rising from the mossy ground under the pines. I was awed by the Halloween specter of a flower on its broom-stick stem as well as the British soldiers with their gray lichen bodies and red caps. Then there were the silvery horns of trumpet moss. Mother carefully transplanted the mosses to make a magical terrarium smelling moistly of forest duff.”

From a letter by Sallie to Watson in 193X.

“Sunday night Ben East a Michigan booster from Houghton was speaker at an evening to tell about the National Park etc. He told what a wonderful thing for Northern Michigan this new national park would be whose automobile trade and tourists were her chief asset.” All the Isle Royalists were so depressed when he got though telling them how “conservatively speaking there would be 1000 a day coming and going on steamers, during the season.”

Rachel Ann McCormick

On December 6, 1906, the SS Monarch a Canadian passenger/package freighter left Port Arthur, headed home to Sarnia, Ontario. This was the Monarch’s last trip of the season and included a robust crew of 30 and a scant 12 passengers. The lone female aboard, was Rachel Ann McCormick, ship stewardess, a farmer’s daughter from Sarnia.

As stewardess, Rachel, age 29, was the assistant cook and most likely had other housekeeping duties. Although stewardesses’ wages were low, conditions were cramped, and hours were long, Rachel, widowed at a young age, could earn a living at a time when opportunities were limited. Census records indicate that Rachel lived with her mother, also a widow, and most likely sought work to contribute to the joint household.

On that fateful December day, the Monarch set sail in heavy seas and snowy blizzard-like conditions. Thrown off course, the ship’s captain missed the Passage Island lighthouse beacon and instead, crashed into solid rock west of Blake’s Point on the northeast tip of Isle Royale, irreparably damaging the ship.

Crew and passengers alit into freezing temperatures. For the next 4 days those stranded lit fires for warmth and ate meager provisions, bagged flour and canned salmon, that had washed ashore. Rachel cooked blackened flapjacks directly over the ashes that were later described as resembling ‘a piece of frozen asphalt block’. A rudimentary tent was constructed from the ship’s sail; Rachel was given the only blanket, a nod to her female status.

On December 10, the Passage Island lighthouse keeper saw their signal fire. A rescue tug arrived soon after and safely transported the survivors back to Port Arthur. When they eventually reached home a week later, a crowd of well-wishers and a brass band greeted them. At this event, the captain remarked to the press: “Every man was a hero but it remained for the woman, Rachel McCormick, one of the crew, to carry off the real honors!”

Information and photos from: Toni Carrell, Monarch: National Register Nomination; Thom Holden, Above and Below: A history of lighthouses and shipwrecks of Isle Royale; Frederick Stonehouse, Isle Royale Shipwrecks; Canadian Census.